Green Taxonomies Around the World: Where Do We Stand?

Following the lead of the European Union (EU), which introduced its taxonomy regulation in 2020, nations all over the world are developing their own green taxonomies. Sustainability-themed financial products have become an important part of the investment landscape. There is a need for a classification system (i.e. taxonomies) to identify activities and assets that contribute to sustainability goals.

What are green taxonomies?

Similar in approach to biological taxonomy, which names, describes, and categorizes living organisms, green taxonomies are used by investors to identify economic activities considered environmentally sustainable, and therefore investment in these activities is eligible for a label of “sustainable.” At the same time, green taxonomies help companies understand how “green” their economic activities are, and businesses can use this information as a baseline to measure improved environmental benefits of their activities.

Green taxonomies are useful instruments, and they have several complementary purposes:

- Taxonomies help prevent greenwashing;

- Taxonomies help investors make informed investment decisions; and

- Taxonomies channel investment toward sustainable or green economic activities and assets.

Structurally, all taxonomies are similar. So far, they all include the goals of climate mitigation and adaptation, and some also include other environmental objectives such as biodiversity conservation, for example. To be considered green, an activity must substantially contribute to at least one of the environmental objectives. Often taxonomies also include “do no significant harm” criteria (i.e. an activity that substantially contributes to one environmental objective should not harm another environmental objective) and social safeguards (i.e. compliance with human rights). However, when you compare the details, they often target different objectives and have varying criteria and thresholds defined for economic activities.

Some taxonomies only define what is green and others, such as the recently launched Indonesian taxonomy or the proposed Singaporean taxonomy, use a “traffic light” approach, where the economic activities are split into different categories (i.e. green, amber, or red) to classify their environmental sustainability. Some taxonomies, like the EU taxonomy, include transition activities (i.e. activities that cannot yet be replaced by technologically and economically feasible green alternatives, but they support the transition to a climate-neutral economy).

Which countries have green taxonomies?

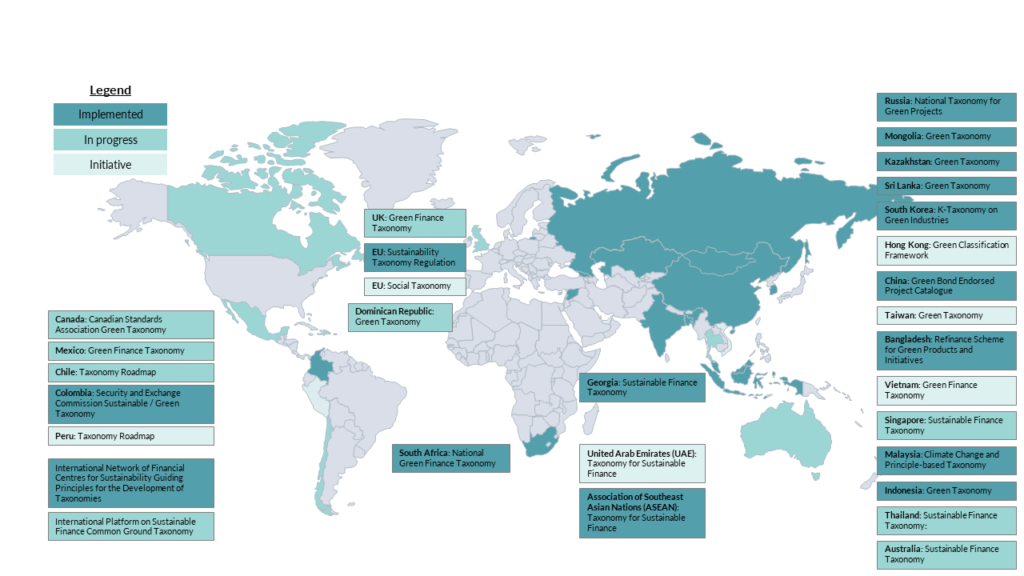

Many countries have either started work on their own taxonomy or finalized one (see Figure 1). Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Kazakhstan, among other countries in Asia, have finalized their taxonomy documents. Latin American countries have also been working on taxonomies fitted to their local context: Colombia is the first country in the Americas to launch a green taxonomy, and other Latin American countries are following in Colombia’s footsteps (e.g. Mexico, Peru, Chile) — the Dominican Republic is the first country in the Caribbean to start developing a green taxonomy.

Figure 1. Overview of green taxonomies and their various stage of development

Why are so many countries developing a green taxonomy?

National taxonomies can help a country tackle its most urgent environmental problems because these tools do the heavy lifting for investors, telling them where financing can be directed to positively influence the climate, the environment, and/or social issues. Countries are aligning their green taxonomies with objectives that resonate with their country’s overall sustainable development priorities and integrating their taxonomies into existing laws and standards.

Many green taxonomies build on the EU’s taxonomy and are then tailored to the local context. For example, Colombia’s taxonomy prioritizes sectors related to land use (i.e. agriculture, forestry, livestock) because these sectors are responsible for 59 percent of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. Countries like Australia and Chile, where the mining industry plays a significant role in the economy, are likely to focus on transition activities.

Is standardization in sight?

While it is great to see so many countries developing their own taxonomies, there is a risk that a “jungle of taxonomies” will render these tools impractical if there is no interoperability. If jurisdictions classify economic activities differently, this may lead to a situation where a company’s economic activity is considered “green” by one country’s taxonomy and “not green” by another, which causes confusion and makes it difficult for issuers to use green bonds in different markets.

The EU Parliament’s recent proposal to facilitate the use of European green bonds by third-country issuers shows the vast potential of interoperable taxonomies: Bond proceeds allocated in a third country could use a taxonomy from that third country if it is considered “equivalent” to the EU taxonomy (in particular its environmental objectives, substantial contribution definition, “do no significant harm” criteria, and minimum safeguards).

However, the world is far away from a globally standardized taxonomy. Regional initiatives are underway such as a taxonomy in the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) region. There is also an initiative for a Central American taxonomy. These may prove first steps toward standardization. Also, the International Platform on Sustainable Finance (IPSF) is building a tool it calls the Common Ground Taxonomy that will serve as a shared reference point for understanding how environmentally sustainable investments are defined in IPSF jurisdictions.

All posts

All posts Contact

Contact

Photo by

Photo by